Editorial written by Tulane President Scott S. Cowen

The Chronicle of Higher Education – After Katrina: Two Presidents Reflect

April 21, 2006

Be Prepared

On a recent afternoon, I stood before an assembly of first-year students and their parents, and delivered my annual convocation address as president of Tulane University. It was a poignant moment for me. At the end of last August, Hurricane Katrina had forced the university to cancel its fall semester, and there had been times since then that the prospect of recovery seemed nearly impossible.

We had experienced the trauma of a major hurricane followed by catastrophic flooding. We had watched our city fall into despair, desperation, and lawlessness. We had seen our students, faculty members, and administrators displaced for months. We had fought to survive against the odds, repaired what at first seemed irreparable, and faced staggering financial losses.

Now, seven months after the hurricane’s onslaught, we are back at the institution that we fought so hard to save, with 88 percent of our pre-Katrina full-time students in attendance. It is with mixed emotions that I review what we have learned. The experiences of Katrina have changed every single person who lived through it in different but fundamental ways. Lessons born of disaster, both institutional and personal, are by their very nature hard lessons.

On the institutional side, we have learned that the emergency plan that Tulane had in place was relatively sound, as far as it went, but it didn’t go far enough. In fact, the plan had been test-driven several times before when the area had experienced a major hurricane threat from a Category 3, 4, or 5 storm. The plan called for a campuswide evacuation, and twice before we had lined up buses and driven students out of New Orleans until the threat had passed. Until Katrina the threat had always passed. Now we realize our plan didn’t consider the possibility of catastrophic damage, of not being able to resume business at the university for a protracted period of time.

As an institution, we have also learned the following:

Don’t let the captain go down with the ship if you want to salvage it quickly. Our plan called for several senior administrators, including myself, to stay on the campus and ride out the storm. It pains me to say that was probably not the best idea. I, along with our senior financial officer and senior communications officer, was stranded on the second floor of a building on a flooded campus for four days with no electricity, water, food, sewer, or reliable means of communication. Our ordeal makes for great cocktail-hour stories — of paddling around in a canoe scrounging for food in inundated campus buildings, of hot-wiring golf carts and siphoning gas for a hastily rebuilt motorboat, of commandeering a dump truck and making a daring escape to a waiting helicopter to finally get out of town. While I wanted to be on the campus and, in many ways, still think my place was to be there, I also realize that I lost precious days of recovery time simply trying to survive.

Recognize that the university is not a shelter. Some employees took refuge with their families and even pets in campus buildings, particularly in our downtown health-sciences center. They, too, were stranded by the floodwaters, and my senior administrators and I didn’t know they were there until it was too late to help them get out. Thankfully, no one was injured, but they placed themselves in grave danger and made the evacuation process even more difficult. We must communicate better with our employees about what they should and should not do in an emergency.

Prepare to stay in touch. We had 6,000 employees scattered to the winds with no way to contact them. All of our systems were backed up, but everything was stranded in New Orleans. Perhaps most important, we have learned that it is crucial to back up all IT systems in a remote location.

As we set up our “recovery” administrative team in Houston, we had to figure out how to find our people using a single campus phone directory and our emergency Web site, which asked them to register their contact information. We eventually heard from most of our employees, but we now will also make sure they know to go to the Web site as soon as possible after an emergency.

In addition, although the Web site worked well once we got to Houston and got it back up and running, during the storm and its immediate aftermath, none of our traditional forms of communication worked — not telephones, cellphones, or computers. The only thing that we could use was text messaging, so we plan to give all essential personnel that capability from now on.

It is also important that all employees set up automatic deposits for their paychecks. We learned in Katrina that even if we knew where our employees were, the mail systems in many parts of Louisiana and the Gulf South were simply not working.

Identify a remote location to which an emergency administrative team should report soon after the event. Eventually we coalesced in Houston, and I would like to say that it was planned in advance. But it was sheer serendipity that my chief of staff evacuated to Houston. And, fortunately, he had the presence of mind to get hotel rooms and office space for us right away.

Be as physically self-sufficient as possible. I realized early on that if we waited for the city to recover — for the public schools to open, for available housing to be repaired — Tulane would never reopen in the spring. If we waited for federal aid to arrive, we would never reopen at all. So we worked hard to establish a local K-12 school for the children of our faculty and staff members. We scrambled to accommodate all of our students whose off-campus housing had been destroyed, eventually purchasing an apartment building and leasing a cruise ship.

Stay true to your mission. We had several options available to us after Katrina. First, we could close the university and give up. After suffering approximately $200-million in physical damages this year alone and facing an unknown future, that is not as far-fetched as it might sound.

Second, we could plan to reopen in January, then sit back, see what happened, and hope for a bailout miracle. But that could jeopardize the very survival of the university — academically and financially — and lead to great anxiety for everyone associated with Tulane. Realizing that “hope” is not a plan, we chose a third option: to rethink what Tulane would be in the post-Katrina world and reshape the institution and its mission to remain academically strong and financially viable, both immediately and in the future. The result was a “Renewal Plan” that represents the most significant restructuring of an American university in more than a century. It leaves Tulane a smaller but stronger and more focused institution, one that is ready to face the challenges of the years to come.

Such institutional lessons from Katrina will be reflected in our future emergency plans. But the personal lessons affected us all most profoundly. There were the usual lessons you hear people speak of after a catastrophic event, and I learned that the reason you hear them so often is that they are true. You realize how short and precious life is. You recognize that you should never take even the simplest things for granted. You clearly see what’s important — or not — in your life.

What else have I learned?

Progress lies in how you handle the darkness and the light. All of us who went through Katrina learned a lot about ourselves, at our very core. The days immediately after the hurricane and subsequent flooding were dark days of the soul for most of us. It was hard to see beyond the despair and the destruction. As I flew out of New Orleans toward Houston after being stranded for four days, I realized that I could either focus on the darkness, or I could try to see beyond it and focus on the light.

I chose the latter, and most of those working with me in Houston and around the country to save Tulane made the same choice. I saw others who could not escape the darkness, or at least were impaired by it. I don’t know where the ability to stay focused and positive through a disaster comes from — whether it is just hard-wired into some of us by genetics or it’s a byproduct of our belief systems and environment. It’s difficult for any of us to know how we’ll respond to a crisis until we’re tested.

Heroes can come in unexpected places and with unexpected faces. I witnessed some of the most selfless and courageous behavior in the days following the hurricane that I could have imagined. I saw Tulane undergraduates with emergency medical training working 20-hour days to rescue people and provide relief. I saw other people step far beyond their university job descriptions to take on gargantuan tasks for no reward. I saw the way the higher-education community rallied around Tulane and other affected institutions, taking in our students for the semester and asking nothing in return. It was a humbling experience, an amazing experience, and I am filled with more gratitude than I can express.

How do these lessons carry forward into the post-Katrina world? For Tulane, Katrina has taught us to plan for the worst even as we pray for the best. It has taught us as an institution to stay focused on our mission and goals even in the face of financial and physical crisis. It has taught us the responsibility that comes with our role as the largest employer in our home city — a responsibility to help rebuild our city and heal its people.

I am excited at the prospect of being able to make a difference in the world, of being in this place, at this time, where unprecedented possibilities exist to confront some of the problems facing not only this city but our larger society. And I am grateful, in a way I could not have appreciated before Katrina, to be part of the higher-education community that met our needs not only with compassion but also with action.

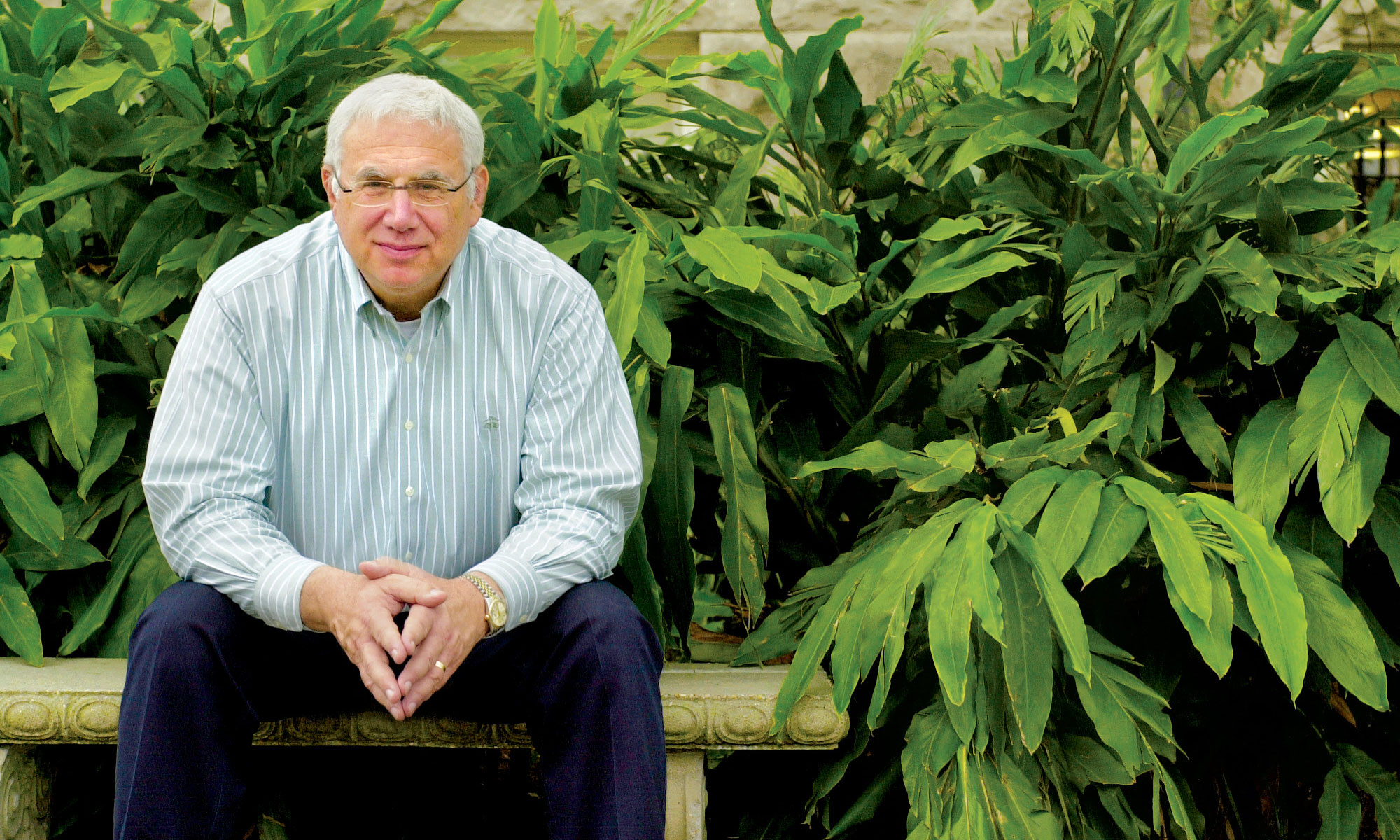

Scott S. Cowen is president of Tulane University.

http://chronicle.com

Section: The Chronicle Review

Volume 52, Issue 33, Page B12