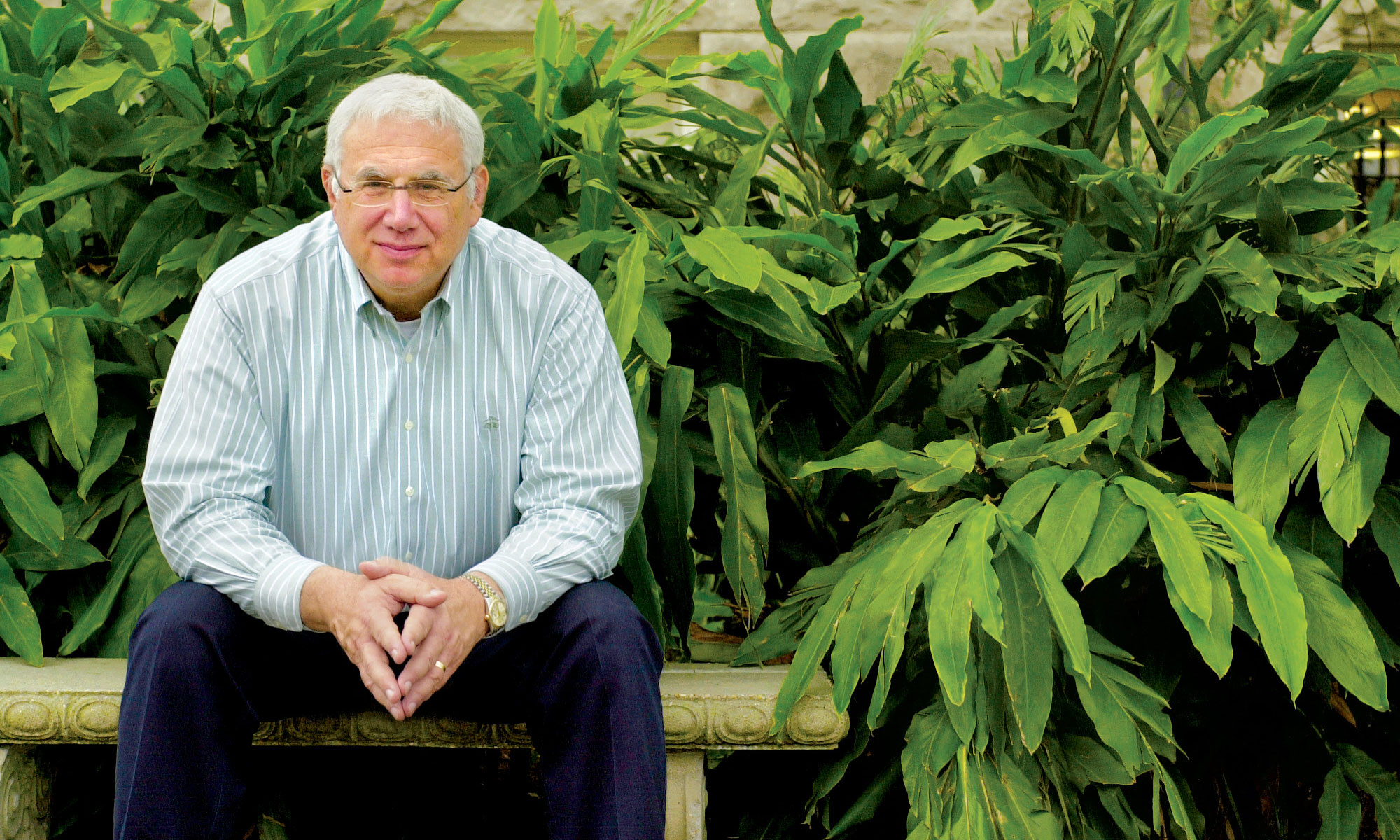

President Scott S. Cowen

Tulane University

September 24, 1998

Setting the Standard

It gives me great pleasure to welcome you to today’s convocation and the opening of the academic year. Today also marks the official beginning of my inaugural year as the 14th president of Tulane University. In my short time as president, I have come to realize that this is the second-best job I have ever had. What was the best? The best job I ever had was being president-elect of Tulane University! I enjoyed that six months so much that I think the position should be institutionalized throughout higher education.

What made being president-elect so special? I was welcomed at Tulane with open arms, intently listened to and rarely disagreed with. I had no responsibility, and was free to say or do virtually anything without being held accountable. I couldn’t do anything wrong!

At the same time, my old colleagues at Case Western Reserve University began to treat me with the respect and reverence afforded an elder statesman. For some unknown reason, they could only remember the good things I did. The tears and kind words I received in the last few months were worth the years of long hours and periodic setbacks that invariably accompany change in the academy.

So perhaps you can appreciate my mixed emotions as I stand here today–longing for the good old days of being president-elect, but eagerly and enthusiastically wanting to lead this outstanding institution into the next millennium. I am honored to be Tulane’s President and thank you from the bottom of my heart for this opportunity. However, I should tell you that being president of a university was never one of my goals. I don’t care much about titles or about position, but I care very much about institution-building–working to make whatever institution I am involved with the absolute best it can be. That is what motivates me. This is why I am here!

As many of you know, the theme for my inaugural year is “Tulane: A Renaissance of Thought and Action.” A renaissance is a rebirth, a rethinking. An opportunity for creative and expansive thinking today about what Tulane can become tomorrow. I want us to engage this year, and in the years to come, in an on-going dialogue about Tulane and what it aspires to be. I trust this dialogue will be deep and rich in its intellectual content and rigor, a real “soul-searching” founded on facts and in the context of the shifting needs of society and the changing environment that surrounds higher education. The outcome of this dialogue should be a sense of where this institution is headed, intellectually and academically. Once this is done, we must act to ensure that our ideas and dreams become reality.

In building an organization, process and dialogue are not enough. As Ernest Hemingway once said, “Never mistake motion for action.” We at Tulane must take the bold steps necessary to secure our future. We must take action, or we will find ourselves either falling behind or–at best–struggling to keep pace with those we now consider our peers. I want more than that for Tulane, and I know you do as well.

It is an interesting time in the history of higher education to become a university president. The environment that nurtured truly influential university presidents such as Chicago’s Robert Maynard Hutchins and Harvard’s James Conant–scholarly visionaries who often set the tone for public opinion–has changed dramatically. Today, pressures both from within and outside the academy have tended to “marginalize” the role of a university president. The “age” of political correctness, higher education as “big business” and unrelenting public scrutiny and criticism have encouraged presidents to say as little as possible publicly for fear of alienating faculty or turning away prospective donors. “Keep your head down,” “Avoid controversy,” “Become the Teflon man–don’t let anything stick to you,” and, by all means, “Don’t speak out on the issues of the day”–those are the nuggets of advice often given to a new president.

So this is the environment in which I begin my presidency at Tulane, and I actually find this to be an exhilarating prospect, rather than daunting or intimidating. What better time to lead an organization like Tulane–already strong, but with unlimited potential–than now, as we prepare to enter a new millennium? We not only have the opportunity to chart the future of this fine institution but, in doing so, to provide direction for others seeking to redefine the “role” of a university in society. I believe–as do many others–that higher education is at a crossroads as our society evolves from an age based on machines and industry to one based on knowledge and information. What are this nation’s priorities at the time of this transition and at the doorstep of a new millennium?

This is the critical question currently facing higher education. It is critical that it be asked by every university aspiring to greatness in a future characterized by fierce competition both for academic acclaim and for the financial resources necessary to reach and sustain excellence.

So, how will we at Tulane chart our future? Will it be “business as usual,” content in the belief that we are already everything we need to be? Or will we have the courage and confidence to take a long, hard look at ourselves and make whatever changes are necessary to secure Tulane’s future and realize its full potential? You can already suspect my answer. No university today–no matter its stature, reputation, or financial resources–can afford to be complacent, because to “stay the course” is to retreat. I believe Albert Einstein said it best when he stated: “Insanity is doing the same thing and expecting different results.”

As we embark on the renaissance that will determine Tulane’s future, I can’t help but reflect on the academic vision that guided this institution’s beginnings with the creation of the Medical College of Louisiana in 1834, the founding of Tulane University of Louisiana in 1884, and the creation of H. Sophie Newcomb College in 1886. Throughout its lifetime, this institution has reflected its strong foundation in undergraduate education, adult education and research. It has been an agent of change and development for the state, the region and the nation. It was built with the classic vision of a university’s fundamental purpose: to generate and transmit knowledge for the betterment of society. Such a simple concept, yet so difficult to execute well. You have made such wonderful progress in fulfilling this vision.

As I reflect on our history, our future, and the role of higher education in responding to the needs of a changing society, I can envision four intertwined images of Tulane’s future. These images are linked together by an uncompromising and unrelenting commitment to quality, impact, focus, and differentiation- always with an eye toward meeting the needs of our society and our nation.

The first image is of a university recognized as one of the most distinguished universities anywhere because it has charted an academic course firmly rooted in its history, location and unique strengths. It is also an institution that represents the best of the modern research university because it anticipates and meets both our national and societal needs at the dawn of the 21st century and beyond.

This image is perhaps the most vital one for higher education and for Tulane’s future. Yet, as I say the words, it seems so ambitious as to be unobtainable. The key to this image for us is to identify what we believe are this nation’s long-term, shared priorities and to internalize these priorities, as appropriate, into everything we do at Tulane University.

Clark Kerr, former chancellor of the University of California at Berkeley, and an outstanding spokesperson for higher education, stated in a recent issue of Change magazine what he perceived were the nation’s shared priorities a generation ago. The first was “…to become the world leader in academic research….” The second was “… to supply the new labor market with people of high skills…” and the third was, “… to create new programs to improve equality of opportunity.”

I firmly believe that these priorities are still very germane to this nation and to higher education. However, the context for these priorities is radically different today than a generation ago. If the higher education system in the United States is to maintain its position of world leadership it must rethink and perhaps redefine its approaches to responding to these priorities. I would like Tulane to be a leader in this effort.

Let me reflect for a moment on just two of these priorities: academic research, including graduate education, and the development of human capital. The third priority, equality of opportunity, is such an important one that I would like on another, separate occasion to speak about higher education’s role in meeting this challenge. I would also like to mention another priority–not specifically mentioned by Kerr–which relates to a university’s role as an engine of change for economic development and community building and renewal. I will address this priority later in my remarks.

After World War II, the United States made a substantial commitment to and investment in academic research, including graduate education, in the sciences and engineering. In hindsight, very few people doubt the wisdom of this investment or the nation’s success in responding to this priority. Yet we must now ask ourselves: What other areas of academic research and graduate education are now necessary to maintain this nation’s competitive advantage in a world increasingly characterized by the rapid dissemination of information, globalization, the realignment of societal, economic and political power, and a widening gap between the haves and have-nots? We can continue to make a strong argument for increased research and graduate education in some of the sciences and engineering. But what are the emerging areas of academic research and graduate education necessary for success in the next generation, and is or can Tulane be a leader in any of these areas? Can we elevate our collective goals in terms of the quality of our research and graduate programs to ensure that we meet the highest standards of excellence in the academy while satisfying the highest academic research priorities of society? If need be, can we redirect our focus and resources from areas of historical importance or where we are not competitive to new arenas of research and graduate education which better reflect the priorities of our future and where we have a chance to excel? Tulane must remain a vibrant, relevant research university, but it is time for us to closely examine all aspects of our research and graduate education activities to ensure their quality, potential, and fit with the priorities of the nation–now and in the future.

As we think about how we need to educate the next generation of leaders for society, can we rethink and perhaps redefine our traditional models of education? Historically, and certainly a generation ago, the widely accepted model for higher education was built on the concept of a student in a campus classroom being taught by a full-time faculty member on fixed days and in fixed time blocks. The student was granted a degree if he or she successfully completed so many credit hours with a certain grade point average. Once the degree was granted, the students became members of the alumni association and their lifelong relationships to the institution became secondary to their own lives and to the life of the institution. This educational model fit the context of a human capital priority a generation ago. It does not fit today’s world, nor does it fit tomorrow’s.

Obviously, there have been changes to the model over time, but in my humble view, these changes have been too slow to evolve and are not nearly creative or responsive enough to meet the needs of the next generation of leaders. I have a strong desire for Tulane to be the leader in defining and implementing a new model of education for undergraduate students, as well as graduate and professional students. In particular, I would like to see Tulane become the research university which offers an extraordinary and differentiated undergraduate experience using many, if not all, of its resources as a research institution. If we can do this, we will have accomplished something others have not been able to do.

I believe the revised model should be based on educating the “whole person” for a lifetime, using whatever technologies and approaches are required to effectively facilitate student learning–at any time and in any place. It is a model that focuses on student learning as the outcome of the educational process and on all parts of the educational experience, not just on the courses taken.

Learning theory has dramatically advanced in the last two decades. Let’s make sure we use the best of these advances to create an extraordinary educational experience for all of our students.

These are just a few of the challenges we must confront and resolve if my first image for Tulane is to become a reality. Start with a renewed and shared understanding of the needs of society in a changing world, and then make sure we attend to these priorities at the highest level of quality possible.

An excellent start in this direction has already been provided by the Strategic Planning Framework Committee with the release of its Environmental Scan report. This report is exceptional in its insight and comprehensiveness. It is just the guide we need to have a dialogue about shared priorities and their impact on higher education. If you haven’t read it, do so. It should be our launching pad for the future.

If we can realize this image, then my second image for Tulane has a high probability of being realized.

My second image is of a university that is a leader, not a follower, in setting the agenda for higher education. I don’t want Tulane to follow in anybody’s footsteps; I want others to follow in ours. At a time of change and transition in society and in higher education, I want Tulane to be the “voice” of higher education and a “beacon” of excellence. Tulane should be a hotbed of ideas and debate on the issues facing our nation and higher education today and in the future. Conferences, seminars, public lectures, websites, and chat rooms are but a few of the vehicles we should use to make sure we are providing intellectual leadership to our students, to our community and to society in general. Community involvement is consistent with an aspiration of being national and international in scope. This involvement must be innovative, of the highest quality and impact, and integrated with our missions of learning and research. If it is, it will be a model for others to replicate around the country.

At a time when universities are shying away from controversial topics, there is an obvious opportunity for a university to fill the void and to become a reasoned and responsible voice for higher education. Let it be us. However, as we assume this mantel of intellectual leadership, let’s make sure our approach is characterized by professionalism, information, and mutual respect for divergent views. All too often today, discussions of controversial issues become heated, irrational, emotional, fear-laden, and personal. Substance too often looms in the shadow of appearance, and whoever can talk the loudest, the fastest, and the most glibly wins the day. If we are to become a voice for higher education, let’s do it in such a way that we not only draw praise from supporters, but we also draw respect from those who may not share our views.

The third image I have of Tulane is of a university in service to the public. A university truly committed to economic development and to building and renewing the communities in which its people live and work, from those in New Orleans and Louisiana to those in the far reaches of the world where Tulane has a presence. We should use these community experiences to strengthen and differentiate our learning and research efforts.

I believe this image coincides with a national priority of increasing importance, that is, to address the urgent social problems of our communities that impede their growth and development.

This image is shaped from two experiences in my life. The first is the 23 years that I spent in Cleveland, Ohio, witnessing and participating in the revitalization of a city on the brink of collapse. In the late 1970s, Cleveland was on the verge of financial bankruptcy and was a national joke on the late-night talk shows. Out of this crisis arose a partnership between the private and public sectors. This partnership crafted a vision for Cleveland’s future and a plan for its revitalization.

Cleveland is now the model used by others truly interested in and committed to urban renewal. I witnessed firsthand the negative impact the city’s image and problems had on CWRU, which is located within the city. Fortunately, I also witnessed the positive impact the city’s turn-around had on the fortunes of the university. I learned a very important lesson from these experiences. A university–or, for that matter, any organization–is highly dependent on the health and image of the community in which it exists.

Tulane University is the largest private employer in New Orleans and one of the largest private employers in the state. It is our duty and responsibility–and it is in our best interests–to find more and better ways to help build and renew this wonderful community by addressing many of its problems, and to spur economic development. We also need to do this in all the communities in which we live and work around the world, and to configure our involvement in such a way that our experiences are integrated with and strengthen our educational and research efforts. This does not mean that we can or should be “all things to all people” in resolving problems or that “anything goes” in the name of economic development; instead, it acknowledges that we want to be an engine of change and development for our economy and community in responsible and appropriate ways.

The other factor that has shaped this image for me is the overwhelming empirical evidence that exists between the growth of economic development within a region and the existence of a strong, vibrant research university in that region. It is difficult to have a healthy and robust economy and community without a research university. A research university has the breadth and depth of intellectual and human resources to spur technology transfer and create jobs. These universities are often net importers of intellectual talent to a region that would not otherwise be there without the existence of the research university. Tulane is uniquely situated in Louisiana and the South to be the model that facilitates technology transfer, job creation and the improvement in the quality of life for the people in our communities. We are already doing an admirable job in responding to community needs, but we should do even more and make these community efforts an integral part of everything we do at the institution. Whether it is community service for our students, or technology transfer resulting from our research, or being the best model of education anywhere, or doing innovative demonstration projects such as the HUD/HANO initiative and the National Center for the Urban Community, Tulane should be a leader in addressing the urgent problems of our communities and being a source of renewal. Whether the issue deals with K-12 education, the environment, welfare reform or other equally important social topics, let’s define an appropriate role for us to play.

My fourth image of Tulane is of a university acting as a community with shared aspirations, values, and goals. It is an institution where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and it is moving in unison to achieve its aspirations and goals. It is a community where members welcome diversity of all types, and retain and applaud certain values, including academic freedom and shared governance.

Last week, the President’s Cabinet sent a memorandum to the Tulane community describing a set of core values that will define how we plan to interact with one another and with others. These values are:

- Humanity;

- Openness;

- Integrity;

- Courage;

- Creativity;

- Excellence.

The public distribution of this memorandum was a risky endeavor for the group, not knowing how people on campus would react. Would there be cynicism, outrage, ridicule or merely indifference? Yet the group felt it was important to set the tone and direction with respect to this image. If we don’t lead by example when it comes to these values, how can we expect anyone else to adhere to them? If we don’t stand for anything, how can we lead?

An essential part of these values is our commitment to freedom of speech and shared governance–values common to most truly great universities. Yet, just as we embrace these “traditional” values, we believe greater discussions must occur about the application of these values in the rapidly changing world of higher education. Hopefully, we will have the foresight and courage to redefine the context in which these particular values exist and to advance them in positive ways understandable to those who often criticize us because of them. All too often, we become defensive in our advocacy and unwilling to examine any possible changes to these values for fear of losing them. I firmly believe these values are critical to our future, but I also believe we must be able to re-examine how they are implemented in light of the current and future environment of higher education.

So that is my fourth image–Tulane as an institution that adheres to a set of values that define its culture and interactions. An institution rich in its diversity and always open to new ideas and people. An institution that is moving together to achieve a shared vision of its future. Together, we must set the tone and timbre for this institution.

Those four images represent my concept of what Tulane can become in the next decade. It is up to you to assess their worthiness and help to develop the concrete ideas and courses of action needed to make the images a reality.

As I reflect on the images, the key success factors to realizing them are to:

- Have an uncompromising devotion to the highest-quality academic standards in whatever we do and always be outcome-oriented in measuring the value of our contributions.

- Create our distinctive way of doing things. Let’s develop an academic vision and set of strategies that clearly differentiate us and focus our efforts in areas where we can clearly excel.

- Invest in the growth and development of Tulane’s greatest asset–its people. We need to have highly competitive compensation packages consistent with an expectation of high performance. We need to provide the personal and professional opportunities for our people so they will have the needed knowledge and skills to be successful. I care deeply about all of you and I want you to have the resources you require to lead productive lives and careers.

- Redesign our organizational structures and systems to be consistent with our academic priorities. Once we determine our academic directions, let’s make sure we are properly organized and have all the appropriate systems–academic and administrative–in place to realize our academic blueprint.

- Raise an obscene amount of money to underwrite our dreams and secure our financial future, and finally,

- Lead and manage this institution in an exemplary manner befitting the best-run organizations anywhere in the world. This is a “tall” order, especially in a university setting, but one we must do if we are to be worthy of respect and support.

All of us share the same basic desire–to make Tulane University the very best it can be, a place where the “best and brightest” students, faculty and staff want to be more than anywhere else–the “first choice” for everyone associated with this institution–a university recognized, applauded and praised by others. You have made remarkable progress in the past in building the stature and reputation of Tulane. Let’s build on this foundation together and go even further.

Faculty, staff, students and all our external constituencies play a vital role in helping this university realize its potential. Let’s respect each other, help each other, and work together. Let your creative juices flow, and we can and will make magic together.

Is this a dream? Probably–but I do believe in dreams. Woodrow Wilson once said, “We grow great by dreams.” I believe in those words, whether they are applied to individuals or institutions. I believe them absolutely and wholeheartedly.

I want to end with one final thought about our future. In July, I had an opportunity to meet with a small group of presidents and professors from several very distinguished universities. These are people I had asked to be my mentors as I make the transition from dean to university president. At a break, one of the presidents asked me to think of a metaphor for what I hoped Tulane would become. I thought for a few moments, then said that the first thing that had come to mind was the Cleveland Orchestra–I hoped Tulane could be like the orchestra. Hearing the answer, he asked me to explain. So, like any good student, I did.

The preceding Saturday morning in my office, I had been listening to a CD by the Cleveland Orchestra performing a Beethoven symphony. At first, I barely heard the music through the focus of my work, but ever so slowly, it began to enter my consciousness. It was incredibly beautiful, so beautiful that I find it impossible to adequately describe in words. I could hear the orchestra as if I were listening to it live in Severance Hall. I got so engrossed in the music and its splendor that for a moment I closed my eyes and was in another world. I was truly moved and transformed by the experience.

So what does the Cleveland Orchestra have to do with my hopes for Tulane? The Cleveland Orchestra is considered a treasure in the city of Cleveland. People adore it, worship it, and support it. The orchestra is a constant source of pride. Yet, just as it is very much a local organization, it is truly international, performing to sellout crowds around the world.

The orchestra comprises approximately 104 musicians, each performing at the highest level of artistic achievement. Each musician has his or her distinctive style and individual talent, yet when combined, these individuals collectively make the most beautiful music imaginable. And, of course, there is the conductor, who is both leader and loyal follower, who can bring out the very best in each person, get everyone to perform together with brilliance, and develop the individual and collective talents that make this orchestra truly world-class.

To make this orchestra work, it also requires hundreds of people in the background doing their jobs one-by-one and getting very little credit. Yet these people provide the context and environment for the musicians to perform at a world-class level.

Finally, there is the audience, always gracious and loyal, returning and giving year after year in appreciation of great performances and comfortable in the knowledge that they have heard from the best.

You, my faculty colleagues, are the world-class musicians; you, my staff friends, are the ones that create the environment necessary for the successful performance; you, my student friends and others who are a part of this university, are the audience we hope for. And me, I am your loyal conductor–not always perfect, but always trying to do his best.

Together, we will create the symphony of Tulane’s future. Our individual talents and skills, when combined, will make this university the place where others want to be. Great music played by and supported by the best talent, always in sold-out performances. All of us together, setting the standard for others.